Dear Charlotte, thank you for sharing some insights into Viking Gold! You co-curated the exhibition with Professor Isabelle Dolezalek while also pursuing doctoral research on gold treasures as objects of identification in the Baltic Sea Region. Could you tell us more about your transition from art historian to curator? Has the collaboration with museum professionals influenced your academic approach?

Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity to present our exhibition in this interview! It was indeed quite a new experience for me to be a curator, even though I do not think of it as a transition, rather as an addition to my skills as an art historian. I think some of the most valuable experiences, which were also great fun, were to find out how to adapt academic knowledge to the desires of an interested public. As academics, we are usually producing incredibly long texts with few images (maybe a few more in the field of art history). Here, we had to condense what we wanted to say to a minimum and make it visually attractive at the same time. So together with our fantastic creative colleagues at the exhibition lab museeon in Berlin, we had several sessions drawing, clipping, highlighting, arranging and re-arranging our ideas with a lot of colourful pencils, papers, stickers and magnets. Apart from creative inspirations for my own working processes on the PhD thesis, I think being forced to condense what I found in the archival material into a few precise sentences also helped me to think more clearly about what I want to say in the different parts of my thesis.

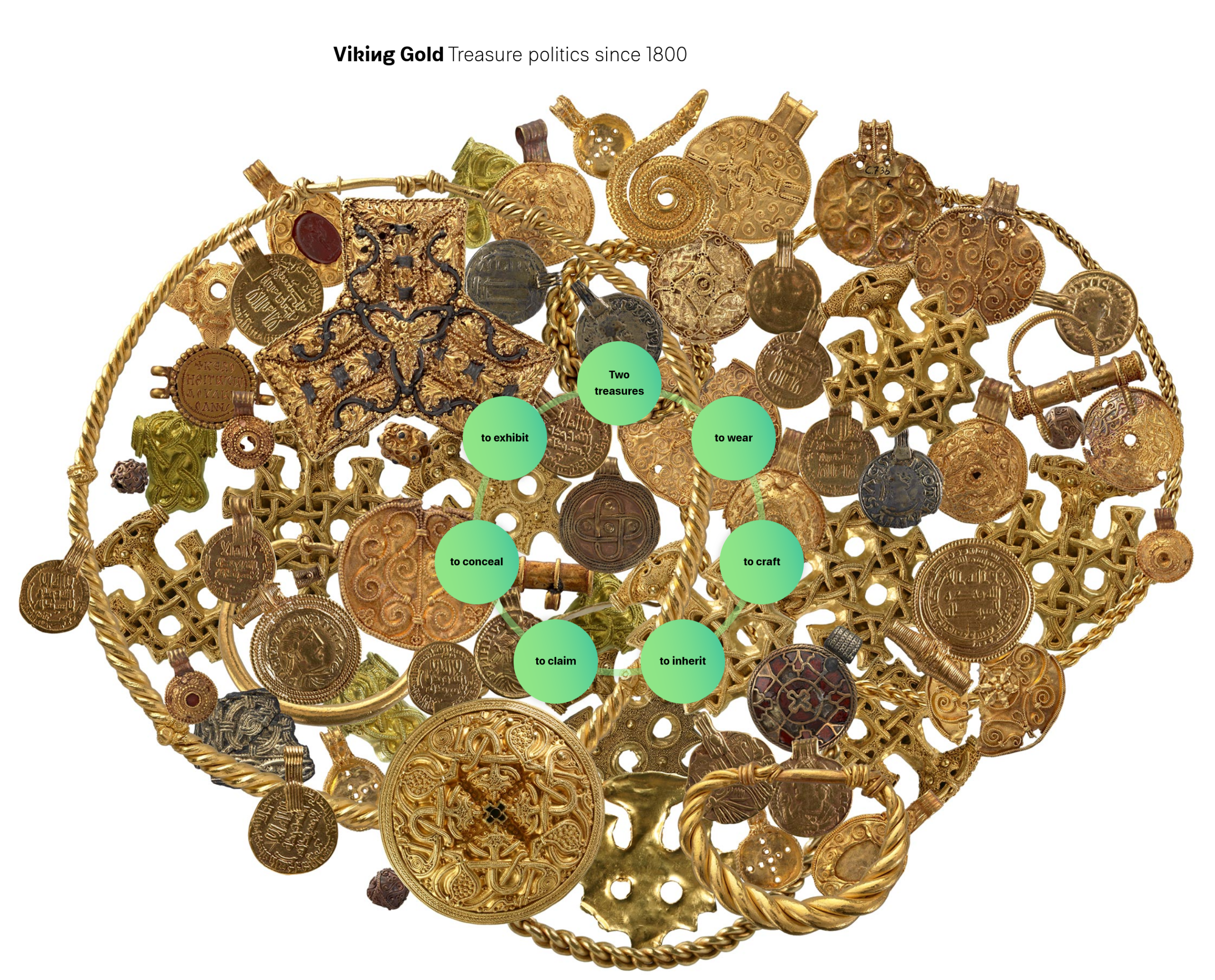

The exhibition highlights two remarkable Viking gold finds: the Hoen Hoard and the Hiddensee Hoard. Originally prized as luxurious jewellery in the Viking Age, these treasures gained new significance as ‘cultural heritage’ following their rediscovery in the 19th century. They have been displayed in national museums, used for propaganda in National Socialist Germany and the German Democratic Republic, and replicated for personal or political expression. How did you trace the treasures’ complex histories? Were there any findings that particularly surprised or challenged your initial expectations?

In my work for both the exhibition and my thesis, my findings are based on a careful investigation of photographic and written source material concerning the reception of the treasure finds after they were unearthed in 1834 (Hoen) and 1872–74 (Hiddensee). These materials are mostly kept in the archives of the museums in Oslo and Stralsund, which acquired the finds shortly after they were discovered and have kept them in their care since. For my thesis, I have been looking for documentation on their acquisition, their classification, their exhibition, their replication and their circulation to other museums. I want to find out how they were used to construct ideas of cultural identity and heritage, and how the museum as institution contributes to this.

For the exhibition, we chose specific aspects of my findings and turned them into seven chapters. One shows, for example, that the same groups of objects can be perceived as ‘belonging’ to different social groups: to a nation, a region or even Europe or the world, sometimes all at once. I think my expectations have not been challenged too much so far, but I found the political impact on the exhibition of Viking Age gold striking. For example, parts of the Hoen hoard were displayed in an exhibition illustrating cultural connections between Norway and the Soviet Union on the occasion of Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to Oslo in 1964 – and in the same year the replica of a Viking Age gold spur from Norway was displayed in the USA. Viking Age gold treasures were used to represent historic contacts with both the SU and the US during the Cold War!

From their Viking origins to modern museum displays, the Hoen and Hiddensee Hoards have been ascribed different meanings over time. Did you identify any pivotal turning points – or peripeties – in how they were perceived or utilised?

Yes, definitely. After 1945, we see, for example, that the transcultural character of the various components of the Hoen hoard is emphasised much more than before the Second World War. This treasure is the biggest preserved gold hoard from the Viking Age and contains, amongst others, coins from the Eastern Mediterranean that were reworked as pendants in Scandinavia, a Frankish strap-distributor reworked as a brooch, pendants of Byzantine origin, and even a carved gemstone from the late antique Mediterranean, also reworked as a pendant. The widespread provenances of the different objects have already been pointed out in the first publication on it that came out in 1835, only five months after its discovery. However, after 1945 the transcultural character of the hoard seems to have made it suitable for the illustration of a shared European past, which was at the heart of European cultural policies after the war. In 1954, it was part of an exhibition in Brussels and Paris that was supposed to popularise Norwegian art in Europe and to contribute to international understanding during the Cold War. In 1992, it was shown in an exhibition by the European Council on the integration of ‘the North’ into a European cultural sphere, and still today it is displayed as a testimony to the transcultural entanglements of the Viking Age. (Check the chapter “to exhibit” of our exhibition for more!)

In what ways have these treasures contributed to shaping regional and national identities in the Baltic Sea Region?

I would say that the Hoen treasure needs to be seen in the context of the impact that the Viking Age had on Scandinavian national identities: In the second half of the 19th century, historians in Denmark, Norway and Sweden adopted the term ‘Viking Age’ in their national histories as the transition period between Pagan and Christian times. Due to the recorded activities of Viking Age Scandinavians outside their homelands, this period was perceived to be the time when these countries became part of (Western) history and ‘civilisation’, as one would have called it in the 1800s. Material culture of the Viking Age, like the Hoen treasure, had an important status as testimony of this period, as there are almost no written sources from Scandinavia from that time. Museums again were among the most important communicators of the newly written national histories, as they were in custody of the material culture. So, from 1904 onwards, the Norwegian collection of antiquities in Christiania (today’s Oslo) had a whole room dedicated to the Viking Age, whose centrepiece was a customised display case presenting the Hoen treasure in all its magnificence. We can imagine that Norwegian visitors to the collection looked at the precious gold objects as one of the prime products of ‘their’ national history.

It is probably no big surprise that treasure finds from the Viking Age have been perceived as national heritage in Scandinavia, but also the Hiddensee treasure has been presented as part of a national – German – history. Both in 1880 and 1936 it was displayed in big exhibitions with a national focus, and even in the GDR, postage stamps depicted one of the treasure’s pendants, which thus travelled the world as East German archaeological heritage. However, in contrast to most of the Scandinavian gold finds, the Hiddensee treasure became part of the collection of a regional museum instead of a national one. This also led to a growing popularity of it within the region of Western Pomerania, where Hiddensee is located. To this day, goldsmiths in the region sell miniature replicas of the treasure’s components as jewellery, and you can find everything from tea cups to biscuit cutters featuring its motives. Both today and 150 years ago, women wore replicas of it to show their connection to the region. Here we can see that this particular treasure find has become important for people’s everyday lives beyond the walls of the museum that keeps it. (Check the chapters “to wear” and “to claim” of our exhibition for more information about that!)

An online exhibition undoubtedly comes with certain challenges. Did you face any difficulties in presenting these objects and their histories digitally? Conversely, did the virtual format also offer new possibilities, for example in reaching international audiences?

As with every digital representation of artefacts, it is of course a pity that you do not get to see the original pendants, rings and brooches – their size, their reverse sides and their gleaming surfaces, which are so specific to gold. On the other hand, the digital reproductions of the treasures travel the world, thanks to the internet. We could indeed see that we were able to reach international audiences. However, this is not happening on its own. You need to advertise even for a digital exhibition, if you want people to visit it. The digital format made it also possible to present the histories of the treasures in an interactive way, for example as a flow chart or rotating picture galleries. Feel free to try all of these on your own devices or in the analogue version of our exhibition, which is touring the Baltic Sea region right now – We will happily receive any kind of feedback!

Charlotte, many thanks for these captivating glimpses behind the scenes. Wishing you continued success with Viking Gold and your ongoing research!