First impression of the permanent exhibition in the main building. In the back the illuminated wall with the numbers the inmates were given. The picture was taken by Anna Derksen in May 2024.

Together with a small group of colleagues we took our chance during our annual workshop, Resonant Conflicts. Turning Points in the Baltic Sea Region, in Trondheim in May 2024 to visit Falstadsenteret, a museum and human rights education centre located at the site of a former SS-Strafgefangenenlager, called Falstad fangeleir in Norwegian and usually translated into English as Falstad concentration camp. Our group had quite diverse perspectives on the exhibition – combining expertise on Germany, Norway, and Sweden from historical, cultural and literary studies, as well as a shared interest in the ways in which historical events are narrated and remembered today.

Before it became a prison camp, Falstad served as boarding school for supposedly misbehaved boys. After the German invasion and subsequent occupation of Norway in 1940 the already prison-like building awoke the interest of the Nazi German authorities, and in 1941 it was re-designed into a prison camp under the authority of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo). Yet, the authorities also incarcerated prisoners of war (POWs) from Eastern Europe as forced labourers as well as Norwegian Jews in Falstad, the latter being further deported to Auschwitz. After the war, Falstad was re-named Innherad Forced Labour Camp. Given the German surrender and the restored independence of Norway, Innherad held Germans and Norwegian collaborators, partly the very same persons who had before been in charge of overseeing the Falstad prison camp. Disturbingly, from the 1950s onwards, the same buildings were used as a boarding school for mentally disabled children until, in the early 2000s, a museum and education centre were developed.

The first impression of Falstadsenteret is by all means the strikingly beautiful landscape in which it is situated. Surrounded by typical farmhouses and flashy green fields, the building itself is surprisingly small. Yet, a small-scaled model at the entrance provides insight into the former extent of the grounds and additional buildings that were mostly dismantled after the war. Entering the main building, one is led into a bright courtyard that is empty apart from a wooden art installation. There is no information to be found on the ways the space was used historically – a situation that we were to encounter again and again and that is arguably also the biggest downside of the museum’s self-presentation. – Yet, a colleague remembered from previous visits that in the Falstad prison camp the courtyard was used for the daily Appelle, with the art marking the spot where a tree was situated that was occasionally used as gallows.

Left, the model of the former Falstad prison camp in front of the entrance to the main building. Right, the courtyard of the main building. These and all following pictures were taken by Josephine Eckert, May 2024.

Upon entering the building it becomes quite obvious that it is first and foremost a place of education, with several bright rooms for hosting groups and a public library. To visit the historical exhibition, one is led downstairs into the basement, where the friendly atmosphere of the entrance area is countered by dark colours and very little light illuminating only the objects on display. Interestingly, not only the first picture, but literally the first words of the exhibition are “Adolf Hitler”, serving as a way of setting the scene, which is followed by a brief overview on the ideology of National Socialism with an unusually prominent emphasis on eugenics. Could this emphasis, our group speculated, be due to the history of eugenics in Scandinavia during the Interwar Period?

The narration of the exhibition then continues with the German invasion of Norway in 1940, skipping the usual moments of escalation such as the beginning of the Second World War with the invasion of Poland in 1939 that are mentioned only later. As I am myself researching how the so-called Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939 is incorporated into historical narrativisations, I was surprised that in Falstad the non-aggression-treaty between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union is nowhere to be found. Stalin is portrayed once next to a picture of Mussolini, but receives no further explanations.

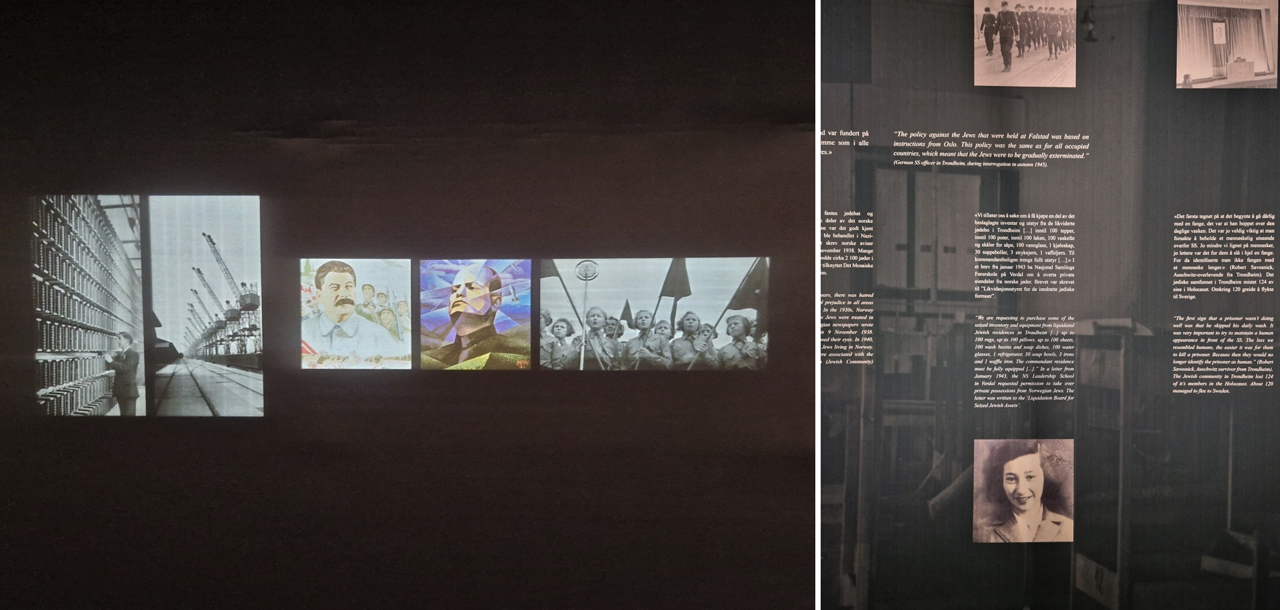

Continuing, the narration focuses on the persecution of Jews in Norway, among them those who had fled the rising antisemitism in Central Europe during the Interwar Period. Accompanying the written text is a picture of Cissi Klein, a Jewish girl who was taken from her school in Trondheim and ultimately deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered at only 13 years old. As my colleagues shared with me, she is commonly considered to be “Trondheim’s Anne Frank”. Her picture is not contextualised by text as visitors are expected to know of her significance for the local memorial culture, which also seems to be the reason her picture is shown, even though she was never imprisoned in Falstad. Her brother and father, who were actually imprisoned there, are in turn not mentioned in the exhibition. What the narration conveys in general information on the Shoah in Norway, it lacks in situated references. I want to emphasise here, though, that the persecution of Jewish people under German occupation is deliberately told as a story of collaboration between the occupying forces, the Norwegian police, and the Nasjonal Samling party – I found that not to be taken for granted in the light of ongoing controversies around the topic of collaboration, not only in Norwegian but also in other European societies.

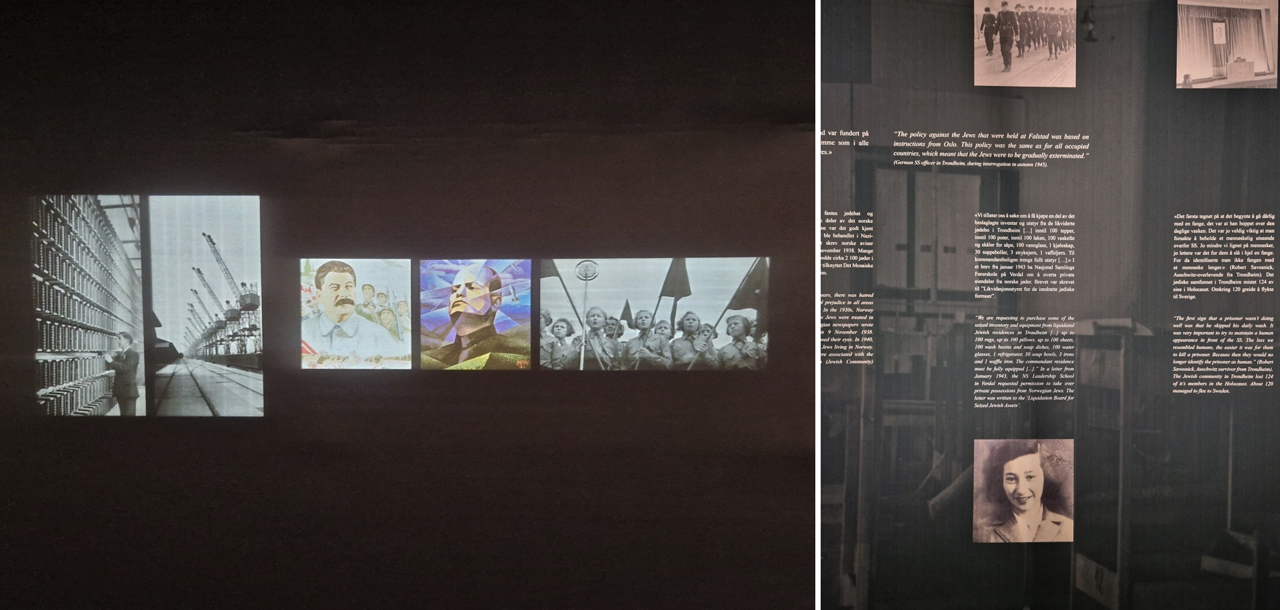

Impressions of the exhibition. The photographs accompany the narration, but are not contextualised, some of them being used several times throughout the exhibition. Left, propagandistic images of Stalin and Mussolini. Right, the famous picture of Cissi Klein.

The main eye-catcher of the exhibition is an illuminated wall with a list of inmates and the numbers they were given, next to several boxes with reproductions of Häftlingskarten (personal file cards). There is no contextualisation, however, of the issue that these evidentiary documents also transport the ideological categorisations of the perpetrator, such as who in these documents is considered to be Jewish and who a political prisoner. What furthermore caught my interest was the way that personal items – those of the former inmates as well as those used by the guards and prison personnel, partly combined in one box (!) – are presented behind dark curtains lit from inside. The arrangement creates a distance between the observer and the observed, a separation of present and history, or even a barrier between the two as one of the boxes was not lit, presumably by accident.

While the main exhibition texts are translated into English, the texts that describe and contextualise objects are not. As I do not read Norwegian, this very much predetermined my experience in Falstad. For example, only after my colleague translated a small Norwegian sign for me that pointed to one of the rooms being a former punishment cell, where inmates were held for several days with water covering the floor to prevent them from sitting down, did I realise that the exhibition was placed in the former cell rooms, a prison within a prison, and arguably a place of torture. One would be right to anticipate the exhibition to further address this haunting history of its own rooms, but the narration focuses more on a bigger picture and less on its situatedness. This also results in a lack of in-depth information on everyday life in the Falstad camp, for example on the back-breaking forced labour.

__________

Part II of this blog, A three-layered memorial, will continue with exploring the Commandant’s House and Falstad Forest and discusses the strategies Falstadsenteret employs in narrating and commemorating its multi-layered history.