Visiting the Falstad Centre in Trøndelag, Norway (part I)

Together with a small group of colleagues we took our chance during our annual workshop, Resonant Conflicts. Turning Points in the Baltic...

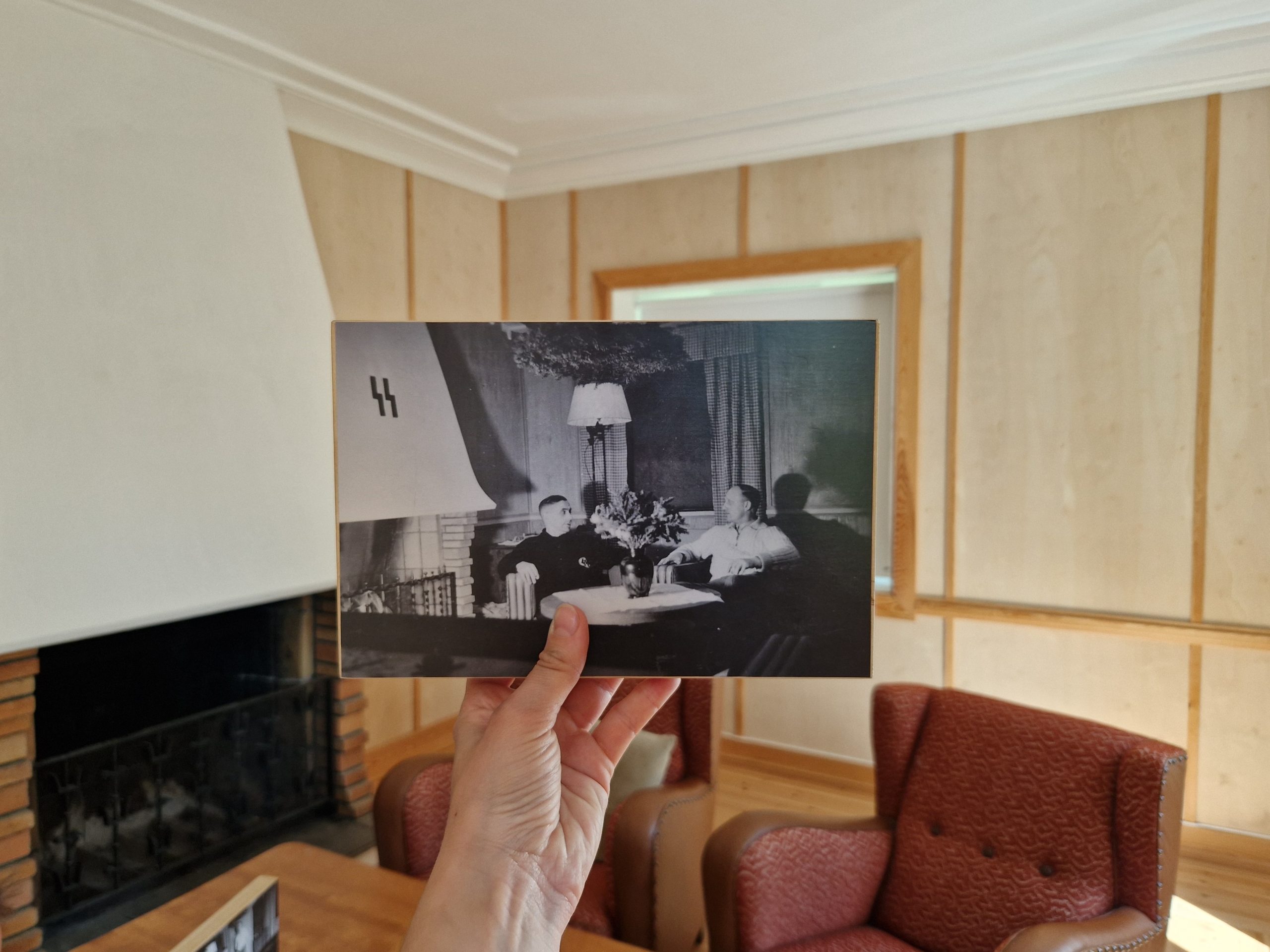

Besides the main building, another historical part of the former Falstad prison camp is preserved: the Commandant’s House, which was built by inmates in 1944 and was home to the final two commandants. After the war, it was used as a private home until it became part of Falstadsenteret. The exhibition Maktens ansikter (engl. Faces of power) was opened in the Commandant’s House in 2021.

Unlike the exhibition in the main building, the house has an overall friendly atmosphere with bright wooden rooms and cosy seating areas. Educational material, catalogues with questions prompting critical reflection, books, contextualised photographs, interviews with witnesses, and art installations are loosely arranged, inviting visitors to dwell and discuss. There are almost no English translations, yet in this workshop atmosphere this makes sense, as it clearly targets Norwegian school and youth groups that visit for the purpose of human rights education.

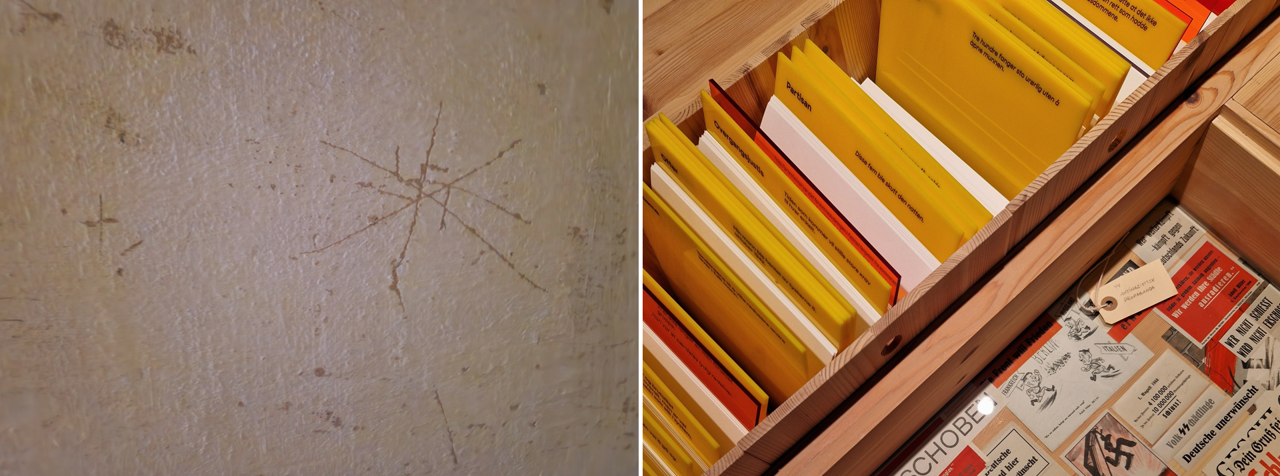

What struck me most was that the space presents itself as an unfinished narrative open for additions. In doing so it invites visitors not only to find their own narrative paths through the exhibited history and to handle some of the objects themselves, but to reflect on their own knowledge in certain aspects. Exemplary for this is the work-in-progress Maktleksikon (encyclopedia of power), a glossary of vocabulary connected to the history of National Socialism and the German occupation in Norway. On the other hand, some visitors apparently also felt invited to carve Swastikas or the runes symbol of the SS onto the walls. It seems that these scribblings are purposely not removed and one can easily see the didactic value in addressing these provocations in working with youth groups – yet, it leaves the visitor (or maybe only me?) with an uneasy feeling.

To finish our visit, we took a 20 min walk to Falstadskogen, the near-by forest and main space for commemorations, marking the place of executions in 1942 and 1943. Among the (known) murdered were 43 Norwegians, mostly imprisoned resistance fighters, 74 Yugoslav Partisans and over 100 Soviet POWs. Since as early as 1947, a commemorative stone centres the memorial site. Designed by the former inmate and sculptor Odd Hilt, Arkebusering (engl. The execution) depicts three Norwegian resistance fighters surrounded by the forest, facing German gunners who in turn are shown against dead tree trunks and fallen branches. Behind the stone, a path leads through the forest, with small stone pyramids marking the spots where bodies were found.

As we learned, 28 Norwegian bodies were identified in the immediate aftermath of the war, their exhumations mostly being carried out by the German occupiers and Norwegian collaborators now held as prisoners at the Innherad Forced Labour Camp. The bodies were sent back to their families and received proper burials. Meanwhile, the bodies of Soviet POWs and Yugoslav Partisans found during the so-called Operasjon Asfalt exhumations in the early 1950s remained nameless and were moved to Norway’s central Russian war cemetery in Tjøtta. Although by now commemoration stones listing the names of some of them do exist, the memorial site at Falstad is still dedicated to the heroic memory of a national resistance movement, paying less regard to the murder of other nationalities and almost none to the shooting of at least six (Norwegian) Jews. In a way, this can be said for the whole complex of Falstadsenteret as depicted in the lack of translations: neither the main exhibition, the human rights education centre in the Commandant’s House, nor the Falstadskogen memorial site address the former victims or their families from outside Norway, as is reflected in the choice of language.

As researchers, we are generally more inclined to criticise than to appreciate. Despite the mentioned obscurities, I would highly recommend to visit Falstadsenteret whenever you have the chance, possibly joining one of the tours if you do not understand Norwegian (I have to thank my colleagues for patiently translating every text I pointed them to for me). Falstad Centre is a three-layered memorial. It provides a worthwhile overview of the history of Norway under German occupation in general and, being situated on historical ground, through Falstad’s past this history is bound back to the local and the personal. Especially the Commandant’s House also gives insight into the ways historical memory is used for human rights education in Norway today, which provided a valuable new perspective for me, as I am focussing on German and Eastern European memorial cultures. Last but not least, the Falstadskogen complex, where we could still see a flower wreath presumably placed there for the festivities on the Norwegian national day (May 17th) shortly before our visit, shows the significance of the history of resistance against the German occupation for today’s national master narrative of Norway.

In light of this complex and still not fully explored history of the Falstad Centre throughout the 20th century – and this text was not even concerned with the history of the boarding schools before and after the Nazis – it is unsettling how Falstad is advertised to tourists. Different from visitnorway.de, I would NOT recommend to stay at Falstadsenteret’s hotel rooms only for their “einzigartige historische Kulisse” (German website) where one might “experience serenity in a rural setting” (English website), but to actually engage with the varying implications of this former prison camp across the times.

___________

Part I, Visiting the Falstad Centre in Trøndelag, Norway and part II written by Josephine Eckert, in cooperation with Paula Friedericke Hartmann (both PhD Researchers in the IRTG Baltic Peripeties).

Together with a small group of colleagues we took our chance during our annual workshop, Resonant Conflicts. Turning Points in the Baltic...

Die skandinavischen Wohlfahrtsstaaten gelten mit ihrer sozialdemokratischen Ausrichtung weltweit als Musterbeispiele für soziale Sicherheit und Egalität. In Schweden hat diese Gesellschaftsvision 1928...

Thank you for your interest in the IRTG "Baltic Peripeties". Our application deadline for 10 doctoral researcher positions has now passed....